Currency (I): Picturing the Value of Any Currency System

When a picture is worth a thousand words

Now that the distinction between money and when it functions as currency is clear (see refresher), it's time to explore why not all money assets can work as currency, why some monetary assets will always depend on another currency, and conversely, why not every currency qualifies as good money. It brings us to the dynamics of the system that give a currency its value. But first, we have to nail down what “value” even means in the context of a currency system where the currency operates.

Value exchange, by definition, is a concept that only makes sense in relation to someone and relative to something else traded. Even the thing you find most fascinating—whether for its properties, like its scarcity that makes it attractive as a hedge to a select few, or whatever reason—is valuable only because others want and demand it.

Take gold: people have liked it for ages, either because it looks great on that watch I’ve been eyeing or because, well, there’s not much gold and it’s a solid hedge against monetary nonsense. Flying cars? Sounds fancy, right? In both cases, value depends on people perceiving them as valuable and actually wanting them. But preferences can change. Maybe people prefer the latest Apple Watch for more functionality or hedge currency debasement with bitcoin over gold, as it’s scarcer and superior in the widely known monetary properties. Or maybe people stick to driving on the ground because they’re scared of the heights that come with flying cars. Nothing’s set in stone, it all comes down to who’s on the other side willing to make the trade for that money, asset or whatever.

So, to understand the value of any currency system, we need to break down what currency value is actually measured against. No currency, purely used as a circulating medium of exchange in an economy (not something consumed or used for non-monetary purposes), has any intrinsic value on its own. Instead, its “value” comes entirely from one thing: people trusting and demanding it to enable exchange for something with perceived value.

The idea in the upcoming contents is to lay the groundwork so you can critically evaluate any currency system value, whether past, present, or future—no matter its architecture and mechanics—so you don’t get fooled. These foundations will help you get ready to use a robust Currency Analytical Framework we’ve put together for you—a comprehensive, adaptable method for evaluating currencies across all possible system configurations. How does that plan sound?

But before…

Love diving into these topics? Join a community of critical thinkers like you, engaging around the workings of money during this transformative “Bretton Woods Moment.”

Join The Hard Money Project Community:

Don’t forget to subscribe for project content updates in your inbox!

Currency system around a balance scale

To get this straight without too much brain fog, as the saying goes, nothing explains this value relationship better than a picture worth a thousand words. Picture every currency system around a balance scale, with the system’s currency on one side and the valuable stuff it buys on the other, all keeping that economy in check.

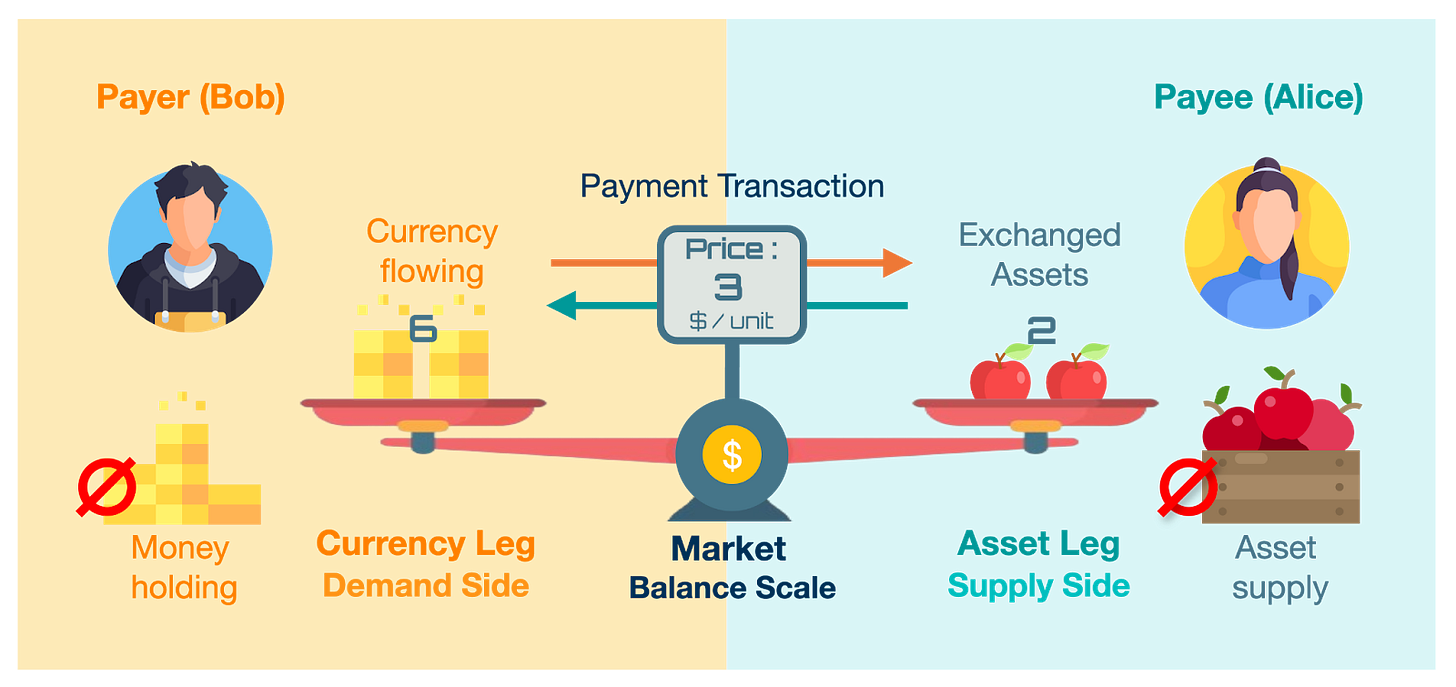

The starting point of every economy? It’s people, at least two of them, who agree on a common medium to trade value with each other. In each exchange, one side brings a stockpile of money (in whatever form, whether coins, cash, physical debt records, or digital records in a database), ready to spend all or a portion of it in the deal, while the other side offers an asset desired by the payer with money—let’s say a stock of apples. Simple enough.

You might be thinking, “So, anything can be money?” And technically, yes, kind of, as history has shown. It can possess better or worse properties, but it only becomes currency when both parties agree to use it in a trade. Once it starts circulating and takes on “direct purchasing power”, its relational value against what’s being exchanged on the balance scale, it crosses the line from a monetary asset to currency. Put simply, a currency economy doesn’t truly begin until both parties agree that this monetary object is the real deal—the common medium that flows through the system facilitating exchange.

Think of it as that moment when Bob, the payer, shows up with his stash of a cool monetary asset—say, a pile of fungible gold coins—and wants to use it to buy 2 apples for lunch. Meanwhile, Alice, the payee, with her supply of freshly harvested apples ready to sell, agrees to accept Bob’s coins—ready to circulate as currency—but sets her terms: she won’t part with 2 apples for less than 6 coins. Bob agrees, and the exchange ratio they settle on, 6 coins for 2 apples (6:2), results in an outcome price of 3 coins per apple. That’s the unit price indicator, or the total currency-to-asset exchange rate.

As you can imagine, in another currency payment, Alice becomes the payer in the demand side because she needs to buy gloves from Matt's shop to collect the apples she just harvested. See how trade creates this dynamic of resource interdependence? Simple.

Now imagine the “balance scale” as that apple market itself, weighing and regulating the currency “spent” on Alice’s apples in each transaction based on the agreed-upon price. But you’re probably thinking, “I don’t negotiate every time I buy apples”. And you’re absolutely right. In a functioning monetary economy with an established currency, the unit price is typically set—whether it’s for a single apple, by weight, or for a bundle like a bag of ten apples—and you simply decide whether to pay it, just like when you’re at the supermarket scanning the price tags.

That price? It’s the signal in the language of exchange that facilitates the whole economy machine running smoothly.

From micro to macro emergence

But as you know, an economy isn’t just a simple swap shop where one type of asset is traded for another. If that were the case, we’d have infinite little balance scales—each representing its own asset-for-asset economy—or, to generalize, what we’d call a barter economy.

A monetary economy, however, becomes interesting when it’s no longer just two parties but others joining the community and agreeing to use that medium (like the pile of gold coins in the example), as a common monetary asset to smooth and coordinate exchanges among them. That monetary asset becomes the go-to tool for trading not just goods and services but also contracts or any other asset of value, effectively flowing as currency—as long as trust in the medium goes just as easily between the parties exchanging stuff.

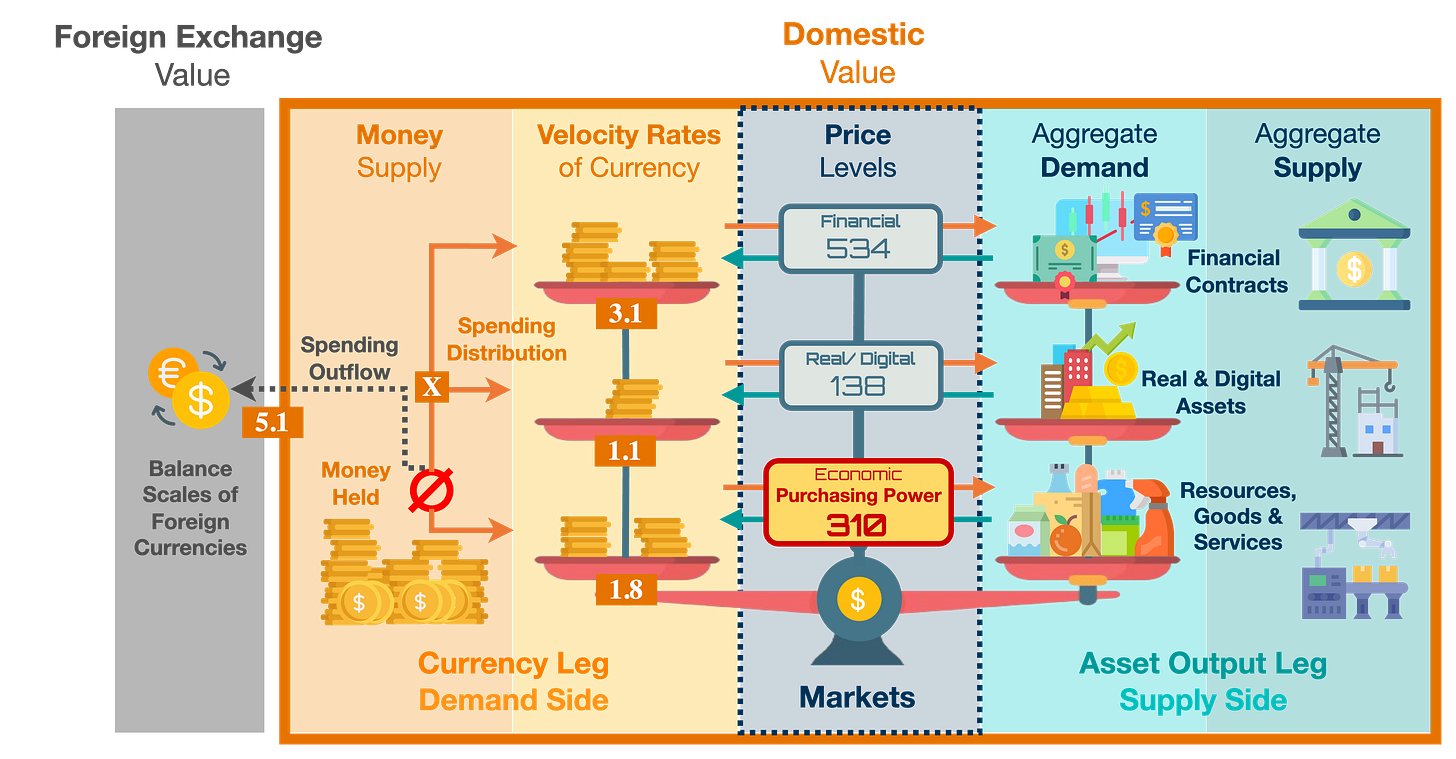

It’s an aggregate phenomenon: picture it as a BIG SCALE balancing countless asset markets. On one side of the weight of the scale sits the currency leg, the money everyone in the community agrees to use for exchange. When that monetary medium adopts some form of standardization—whether in shape, weight, composition, or even digital bits—it streamlines the common denomination of trade, which we call the unit of account. On the other side of that big scale balancing exchanges, you have the asset output leg with everything else—all kinds of assets or valuable property the community considers worth trading for.

So, economic assets, when you dig a little deeper, you’ll find that purchasing power defines a specific type of value: the relationship between currency and the resources, goods, and services (you know, the economic stuff) that the average Joe—and every organization—depends on to keep things moving in their daily grind. It’s a big-picture yardstick for what your money can actually accomplish when it comes to the stuff you need and use every day: from buying groceries, paying your hairdresser, to covering the costs of running a business. And let’s be real, you want it stable over time so you’re not constantly dealing with planning headaches.

Financial assets with payment flows denominated in the respective currency, on the other hand, are essentially contractual tools—designed to transfer purchasing power between parties, accompanied by rights and/or obligations, or to hedge risks that could disrupt purchasing power stability.

Real and digital assets, meanwhile, play different roles. They are more focused on long-term utility, speculative opportunities, or indirect value storage. While they might not directly pay the bills or fill your fridge, they play a crucial role in the broader landscape of wealth building and currency risk hedging.

And, what’s Foreign Exchange Value? As the Picture 2 shows, it’s the relational demand value of one currency, heavily shaped by how well (or badly) its balancing act works on its own scale, relative to another currency with its own functioning scale. Picture it as a third giant market scale weighing the relative demand for exchange between two currency scales—a bridge scale connecting competing scales.

If a monetary asset doesn’t have its own functioning balance scale, it’s not truly operating as a currency—that medium generally accepted to coordinate exchange in the economy. Instead, its purchasing power value becomes indirect and dependent on a foreign currency with a working scale, shifting the asset’s role to something entirely different, like a good hedging asset, for example.

To grasp the direct value of a currency economy revolving around this grand balancing act, you need to break it down. Start with the micro-level fundamentals and work your way up to how these pieces interact over time, shaping the countless scenarios that define the bigger economic picture. So let’s break it down!

[1] Agents

This is where everyone steps onto the stage. By “everyone”, I mean you, me, and anyone else with an identity, standing in every transaction on one side or the other of the balance scale that mirrors the market. Sometimes we’re the payer, sending currency; other times, we’re the payee, receiving it—sometimes in exchange for assets of multiple types, and other times for nothing more than trusted ownership transfers without an asset counterpart.

Agents with an identity can be anyone: a person with the same inherent dignity as everyone else, their delegated programmable digital twin linked to some account in a database (yes, that’s already a thing), or a collective entity like a company, an institution, or a governing body. At the end of the day, all of these are, let’s be honest, just groups of people with rights and obligations tied to that identity.

[2] Money

Money is the community's go-to asset for facilitating exchanges—the star player taking half the spotlight in any currency system. Generally, it steps into action when demanded to circulate as currency for spending on something, adding weight to the balance scale of transactions. So, for the money stock (M) to function as currency at any moment, it needs to weigh in on the respective market scale (multiply) by the fraction/rate of the stock exchanged for something valuable (velocity).

As we explored in Money (I) and Money (II), this institution can take countless forms. It might be a physical commodity, standardized like coins or not, or a representative claim on such a commodity. It could also be a fiduciary medium as debt, with or without collateral backing it—whether in paper form, like the bills we touch, or as data bits recorded in some database. And yes, you've noticed, the digital version is the hot trend, the direction everything seems to be moving, whether we like it or not.

[3] Assets

On the other side of money, in the asset output leg, lies the aggregated supply of all types of assets, each with its own conditions and a transferable bundle of property rights. These assets come into play through the magic of human interaction—someone has to offer them up and put them on the table, first of all. And it’s only when they’re in demand that they tip the asset side of the balance scale, adding weight to the aggregate demand.

Meanwhile, the supplier of those assets, as the payee, receives their monetary reward on the other end of the transaction: currency flowing as income for the value provided, keeping the whole system spinning. Without currency spending, though, supply just sits there without being exchanged—offered but untouched, like leftovers at a dinner party.

These property rights might be implicit, based on wishful trust: for example, you buy a bag of apples at a street market, and if they turn out to be rotten, you expect the seller to replace them or give you a refund (assuming the right to replacement or refund). Or the rights could be explicitly written down, like on a receipt or warranty—a mutual acknowledgment between buyer and seller, with each keeping their own copy. Today, most of these registries that prove ownership rights over assets and their transfer are digitally recorded in centralized databases controlled by the seller or payee.

But here’s the twist: what if that database were a public, distributed ledger—a digital commons that no one controls unilaterally? Imagine a system where you can fully own your tokenized assets' property rights, it's tamper-proof, and ownership transfers happen only according to the terms of the trade agreement. No middlemen gatekeeping your rights. If that’s on the table, could it rebuild trust in exchanges between strangers while cutting down on the power abuses by those running the rights recordkeeping show? Let’s save this deep dive for another day!

[4] Markets

Now that we’ve seen what’s on each side of the scale, let’s talk about the scale itself. Just as humans rely on language to communicate within communities, we use money as the language—or symbolic medium—of exchange within communities as well. And these individual scales? They’re the markets, where different types of assets are traded and negotiated. Put them all together, and you get the grand balancing scale that defines the entire local, community economy.

The aggregate scale is the grand balancing act across all those markets. Each market is shaped by the quirks of its assets, grouped by categories, industries, and whatever else makes sense. Every asset finds its home in its own market, which, as the diagram shows, we can broadly sort into a few buckets in the domestic economy: markets for economic goods (like input resources, goods, and services), markets for real and digital assets outside of any production or service provision process (from the gold you stash to those bitcoins you’re HODLling for a rainy day), and markets for financial asset contracts (whether it’s equity, fixed income, derivatives, or insurance policies by instrument nature). Easy enough, right?

Markets, like agents, money, and assets, can exist in physical forms—like the fruit you buy from a street vendor—or in digital ones, which can be enhanced by programmable mechanisms capable of automating processes, even combining multiple transactions into one. But let’s not forget: at the heart of any transaction lies an action, whether driven by a human decision or a seamlessly connected automated process. That’s where everything starts, and that’s what we need to explore.

[5] Actions & transactions

Now that we’ve mapped out the system around the scale, it’s time to take action. Money and assets may be the stars of the exchange, but none of it happens without some kind of action driving it. And yes, that action is “still” almost always human—powered by individual psychology (“I need coffee now”) or collective decisions (“Our company needs to pay the supplier X”).

Think about it: why do you buy coffee instead of making it at home? Maybe it’s for convenience, a treat, or just because you enjoy how the barista spells your name wrong. These factors: personal incentives, circumstances, and collective needs—drive us to take action. Whether you’re bidding on a rare collectible or paying for apples at the farmer’s market, every trade starts with a human decision, shaped by motivations and/or incentives, big or small.

Therefore, every transaction in a monetary economy starts with an action involving money. These actions break into three broad stages: creating new monetary units that make up the supply, deciding how to use it once it’s out there, or removing them from circulation. And yes, here too, the transaction details initiated by those actions might not be recorded at all or could be stored in a database controlled by someone—or even decentralized today, if we’re talking distributed ledgers like blockchains for example.

A) Minting. The first step for any monetary object, physical or digital, is creating new units added to the money stock outside the balance. These units might be unbacked (poof, money airdropped out of thin air) or backed by assets that can either be purchased or newly issued, such as fixed-income instruments, equity, or something else of value. This process, called “minting” in the currency’s primary market, standardizes money issuance into a form that the economic community broadly agrees to accept. Simple power, right? Create it, back it (maybe), making sure everyone agrees it’s real.

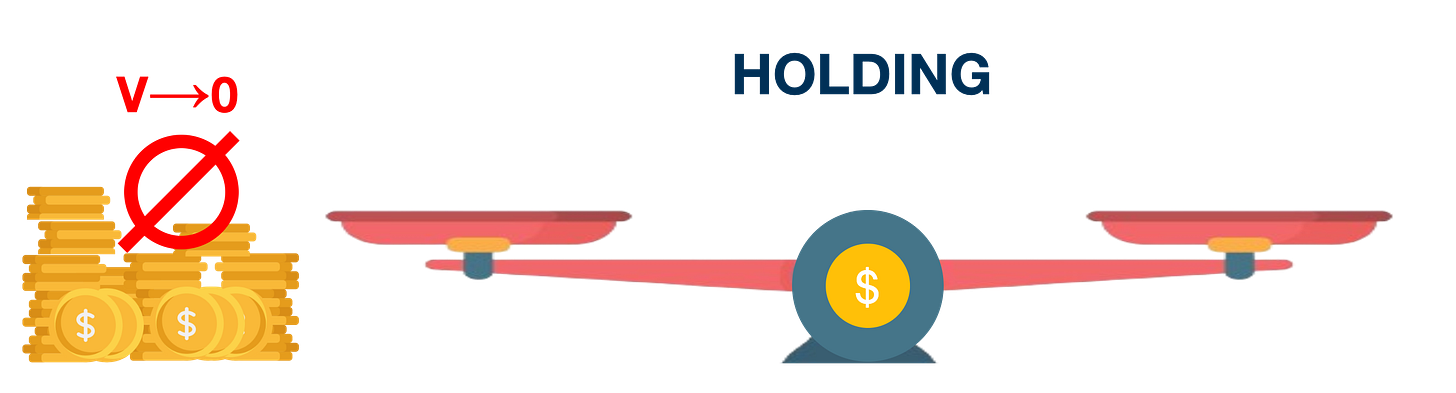

B) Holding (HODLing). It is the inverse force of putting money to work (the velocity rate). Instead of spending or investing, you let it sit inert, off the balance scale, as illustrated. Holding money slows down economic exchange. The longer you hold the medium, the less exchange it facilitates, effectively cutting off any potential income that could have come from trading it for something valuable on the market’s scale.

So, if someone produces a good or offers a service—let’s say Alice’s apples, with all kinds of input costs in the process—but no one demands them with money, no one puts their currency on the scale for Alice to add the priced or agreed-upon apples to the counterbalance, then Alice is stuck holding the bag of apples, waiting for income that never shows up. And yeah, eventually, the apples rot and no income.

Velocity is ultimately a rate—the cumulative rate at which money spending circulates as currency over a given period—it’s like a virtual ratio where each payment adds weight to the currency side of the scale during that time. Then, the lack of transactions, or the tendency to hold rather than spend, slows that velocity down. In fact, the more money is held rather than circulated during the measurement period, the closer its velocity of circulation trends toward zero.

Why hold? Maybe it’s the classic rainy-day fund, saving for future uncertainty. Or maybe it’s the hope of appreciation over time, as demand for the asset increases relative to other assets or currencies, indirectly granting holders increased purchasing power compared to those benchmarked assets. Whatever the reason, holding is all about patience and a little bit of speculation into the future.

C) Transferring Ownership. A currency’s ownership transfer can happen without a direct counterpart—think gifts, donations, or cross-border remittances, with or without foreign exchange conversion.

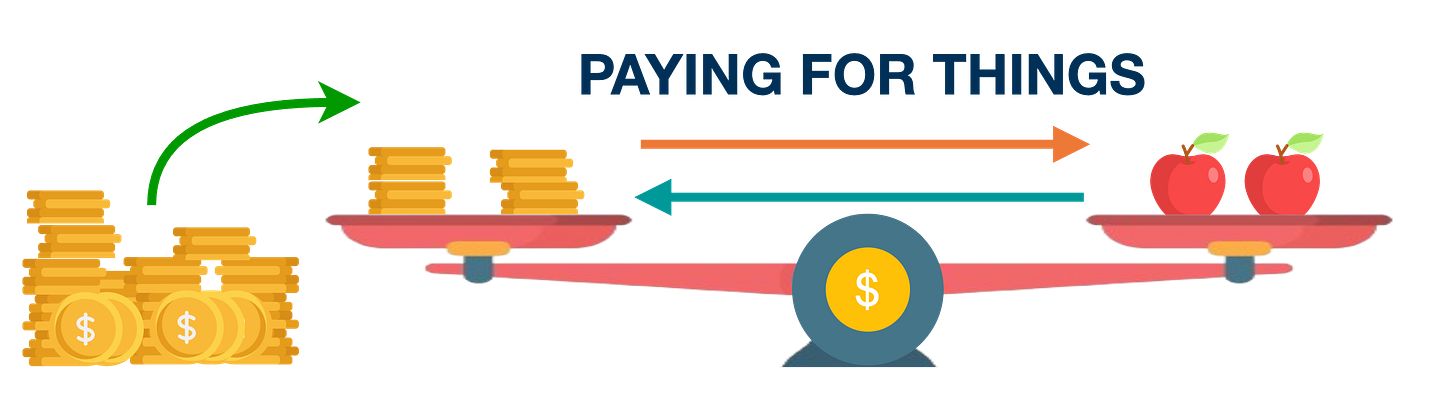

Alternatively, payments for things occur when currency is exchanged for something else with value as a counterpart, adding weight to both sides of the scale. In this case, on the currency leg, weight is added to the “virtual” currency velocity rates as spent balances accumulate over the measured period—rates that may vary depending on the category (i) of asset(s) acquired in their respective markets.

Payment spending also shifts the aggregate balance, amplifying the currency’s role in the broader economy and the income generation that comes with each currency flow for the payee side of the exchange.

Overall, ownership transfers, whether unilateral or part of a cross-asset(s) swap or payment, might go unrecorded, be noted on paper, or exist in a digital database.

The payment transaction—whether push, initiated by the payer using currency, like your regular Venmo transfer to a friend, or pull, initiated by the payee, like your Netflix subscription or a cashier activating the POS terminal1 for your card tap—can be classified by the type of asset added to the scale’s counterbalance, on the demand side of the total output leg as:

Economic: This covers all payments in the same currency denomination tied to productive processes—from raw inputs, like the water or electricity used, to the final product. Whether it’s for creating consumable goods, like that can of Coca-Cola at the supermarket, durable capital goods, like your work laptop, or the provision of services, like an hour of your French lessons. Simply, where the magic of production and consumption happens—without this exchange, there’s no economy.

Real/ Digital assets: These are payments for assets that won’t roll up their sleeves and contribute to the economy’s productive machinery by providing goods or services—they’re bought with the speculative hope that their price appreciates over time. Think of that limited-edition painting you vault away, hoping to flip it for a higher price later or that orange crypto-asset we all know and love. It’s less about creating value and more about relying on perception, scarcity, or speculative interest to boost worth passively.

Financial: This includes payments tied to financial instruments, whether for financing—between financer and borrower (or financed party)—or for risk management, between insurer (or market provider) and hedger. These payments fund contract tools that “may” enable value creation rather than embodying value the tools themselves, moving money savings—existing or newly created—between parties, which is why the “may” matters greatly depending on its purpose for the economy's balance:

Investment or productive finance. Borrowing or raising funds to invest in projects that create real purchasing power value. Picture a company issuing bonds to build a new factory, a startup securing venture capital to develop a groundbreaking app, or equity funding for renewable energy infrastructure. On the flip side, lenders and investors provide the capital, whether from money savings or leverage. It’s money put to work to generate real income and tangible goods or services, with returns driven by a productive process, shaping the economy along the way.

Speculative finance. It is all about borrowing to bet on asset price swings—up, down, sideways, who cares? Whether it’s chasing stock movements divorced from fundamentals, re-leveraging fixed-income collateral (hello, rehypothecation), or surfing the volatility of the latest crypto or meme-token craze, it’s a game of musical chairs. And as long as the music plays, asset bubbles grow, drifting ever further from the economy’s real productive potential… right up until inevitably, someone starts taking chairs away.

Thus, monetary economies with direct purchasing power value are basically mesh networks of payments that underpin every step of the productive process. Think of it like this example: productive financial payments secure funding to acquire assets along with all or some of their bundled rights, whether it's paying for natural resources like water, electricity, capital like machinery or skilled labor, or consumables used in the process. The final output, if it’s durable, can become an input for another process—creating a continuous loop of payments. Whether it’s for a smartphone or for last night’s food delivery service, these payments fuel productive processes and community services, driving the system forward.

D) Removing with or without redemption. Currency units can also be removed from circulation through the same off-scale primary market that originally issued them—whether it’s a bank, a private firm, or an automated digital monetary protocol, regardless of the monetary model. This removal may occur through repaying a debt contract that created the currency, redeeming it for an external asset it was backed by, or directly “burning” the unit to remove it from supply entirely.

[6] Price levels: the outcome

Just like in a local scale market—say, Alice’s apple stand—where the price is the rate of currency units per apple, per pound, or per bag (or whatever units we’re using), a currency system operates on the larger scale. Here, the output is the total currency units spent relative to the total assets demanded over a given period. This aggregate indicator is known as the price level, basically the cost of “a unit of all the stuff in the economy”. But as you can see in the picture 2, there are different price levels across scale markets or asset category types (j).

Which price level matters most? Ding, ding! you guessed it: the price level for economic resources, goods, and services we use in our daily lives. This is the real signal that translates purchasing power as the relationship between the currency and the economic stuff it can buy over time. And getting that purchasing power balance right? That’s the key takeaway people get from any currency system. A signal currently based on weighted product samples provided by government agencies, often with political bias. But could we move to a future where, with tokenization on both sides of the scale, every transaction and price settlement is captured on a distributed ledger, removing the need for third-party agencies?

Also, it’s important to note that price movements can diverge between local markets and the aggregate economy. For example, laptops might get cheaper over time thanks to innovation and capital replacement. Meanwhile, apples might be getting more expensive—after all, an apple is still just an apple, but maybe people value it more than they used to. Yet, overall, the aggregate price level could still be rising.

Dynamic Prices: Some assets operate with dynamic pricing, where each transaction has a marginal impact on the price. You’ll typically see this in financial markets and in the real or digital asset categories. Think stocks or crypto.

Sticky Prices: On the other hand, many prices, like wages or goods in economic asset categories, are sticky. They’re largely unaffected by individual transactions and follow path-dependent trends. Exceptions exist, of course—like your Uber ride, which can surge in a heartbeat.

Takeaways

With all this, you now have a clearer picture of what currency value really means. When someone says, “the value of money is relative”, that’s right, but now you have the nuance to see there’s more behind such a simple statement.

Monetary value, as that relative concept, is measured by what’s actively in use or being exchanged. A currency's direct value comes from the balancing act of its most important attribute: its purchasing power, measured by its ability to buy goods and services that are both priced and willingly exchanged for it.

Indirect value, on the other hand, comes from something entirely different: the value of an asset that doesn’t function as a true medium of exchange itself but instead derives its worth from another currency that does and coordinates economic activity having direct purchasing power.

And yes, if your non-currency asset relies on this indirect setup, you want it optimized for price appreciation relative to foreign currencies, boosting your indirect purchasing power. The more foreign currency it buys, lowering the triangulated indirect pricing of goods and services through that foreign exchange, the better off you are holding that bag. As long as that process keeps working, you can call it a store of increasing value. Sound familiar to any asset you know?

Like it or not, we live in monetary economies, where money is the language we use to measure and signal exchange. If we lived in a gift economy, where actions were driven by reciprocity and everything was free, none of this would be necessary. But coordinating exchange with strangers? Yeah, good luck with that. And don’t forget, in today’s society, you depend on the actions of countless people in countless markets to get by. So let’s coordinate value exchange!

A POS (Point of Sale) terminal is a device that lets businesses process payments when you buy something. It’s where you tap, swipe, or insert your card (or phone) to pay, and it connects to payment networks to transfer currency from your account to the seller. Think of it as the digital cash register that processes payments securely and records the transaction.