Currency (II): Balancing Needs for Every Economy

Dynamically adapt locally to stay stable globally

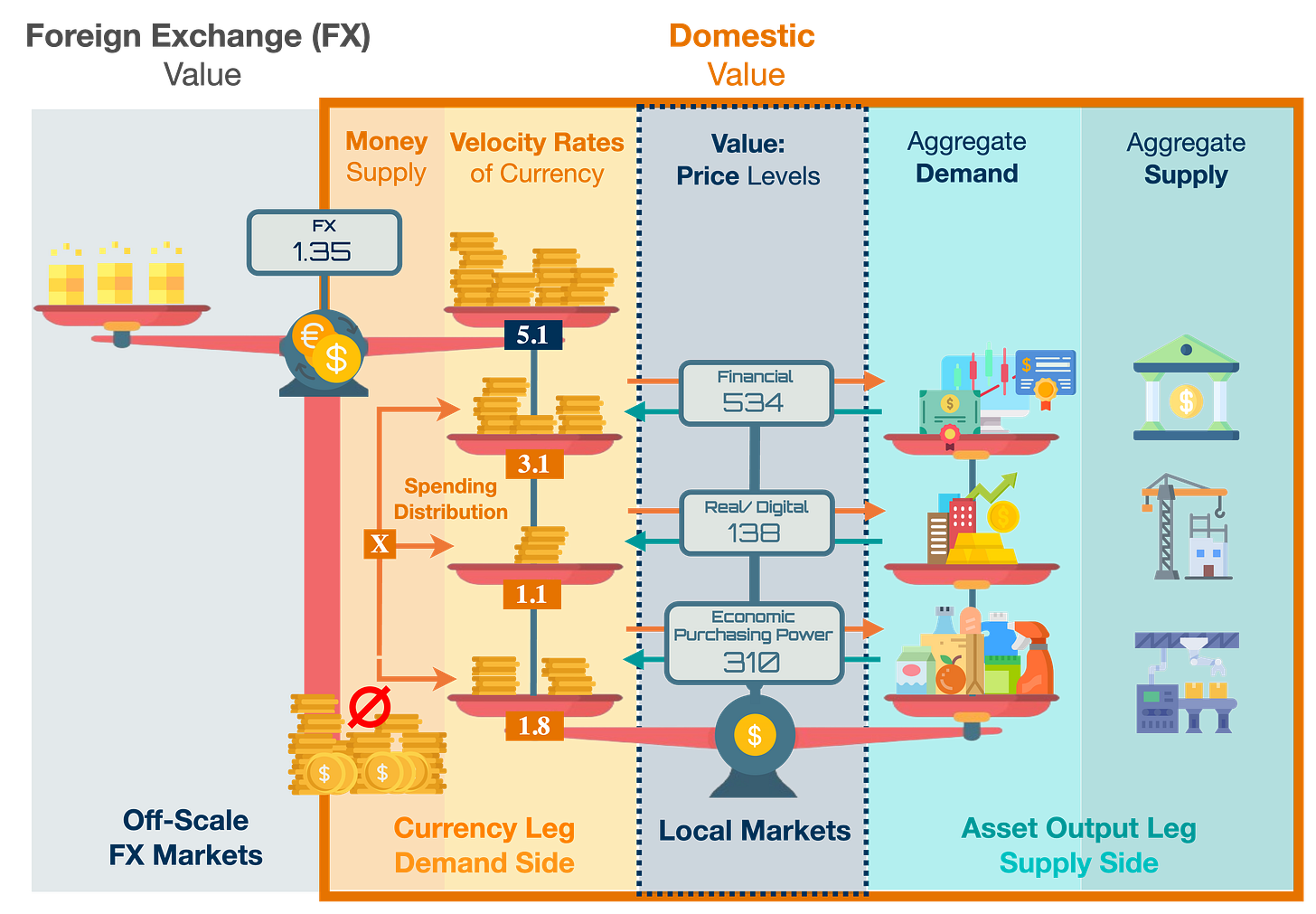

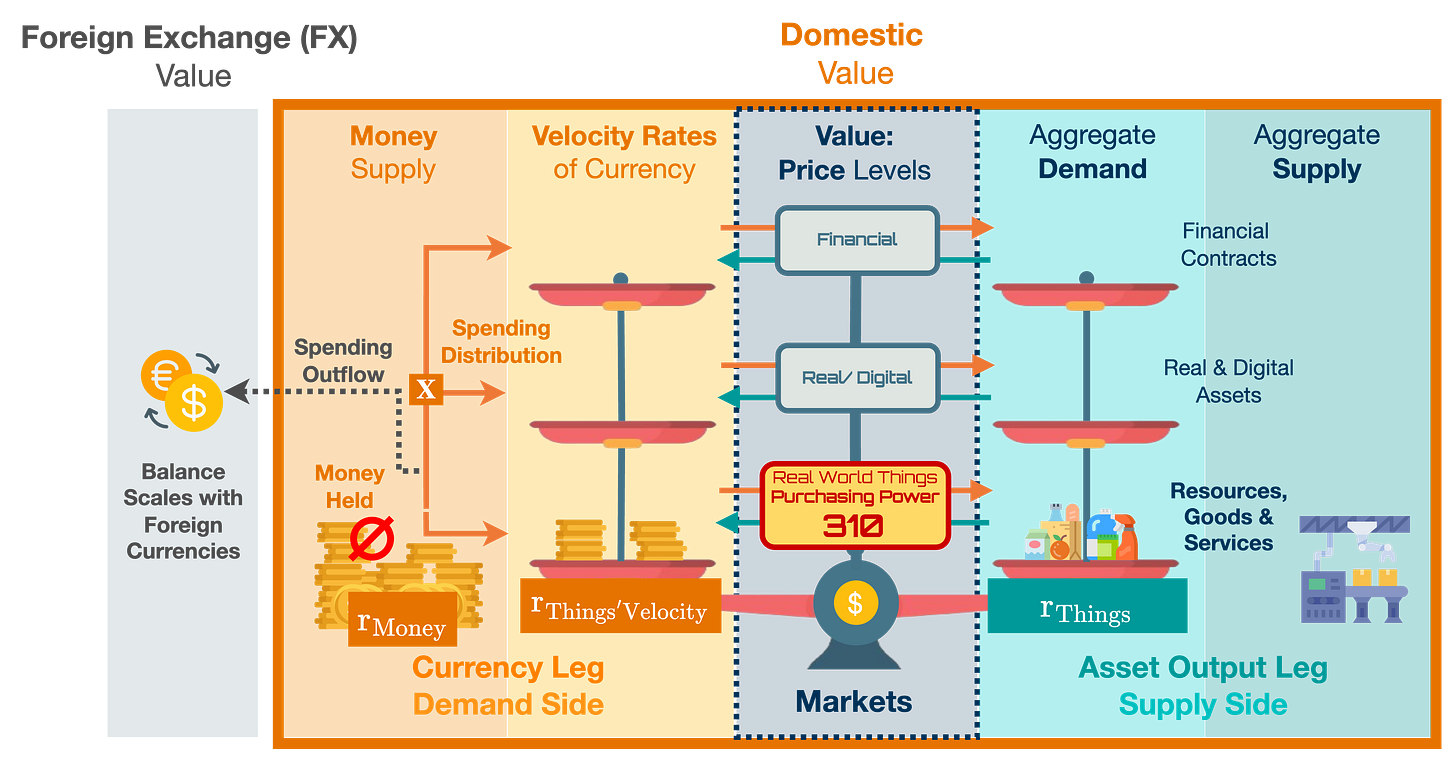

From now on, we’ll picture the value of a currency in a monetary economy as one of those old‐school balance scales—except this one is a big-scale juggle of local currency for markets across a diverse array of asset types. Each tray pair balances the cumulative weight of currency exchanged on the demand side against a category of asset(s) placed on the corresponding supply side tray. That is, everything someone might trade for that local currency: from apples to an hour of massage, a convertible bond as a financial contract, electricity bills, a contracted periodic salary, or whatever resource you can think of.

Meanwhile, there’s only one tray on the currency demand side that isn’t connected to a counterpart on the supply side of the local big-scale. Instead, that tray links to off-scale foreign exchange (FX) markets that weigh its value relative to other foreign currencies, measured in exchange rates. Each foreign currency has its own money supply policy and domestic balancing process for its local economy (functioning better or worse). And those foreign currencies? They could be anything.

With the framework in mind, the question we’re gonna ask in this chapter is:

Can we pile everything onto one big balance scale without it collapsing, or do we need a network of self-balancing local currency scales—coordinating under rules with mutual respect or competing with each other?

Answering this question is more intuitive than it might initially appear. At its core, it’s about whether significant heterogeneities exist on either side of the scale—locally or in aggregate—that cause imbalance. If heterogeneity is minimal, a single‐scale system might suffice; otherwise, the balance must be distributed among multiple, localized self‐sovereign currencies, each tailored to its Optimal Currency Area (OCA).

But before ...

Concerned about the future of money? Join the THMP community and connect with thinkers like you, learning about money in today’s “Bretton Woods Moment”.

Why does this matter?

While we’ll dive deeper into big-scale imbalances of demand side versus supply side in the next chapters, it’s worth previewing why any imbalance without a monetary counterbalancing feedback loop is a problematic. They ultimately result in wealth and income redistribution, deepening inequalities within the currency’s community over time—both internally and compared to other currencies in a stronger position—along with all the local discontent that follows.

Inflationary pressures kick in when the currency leg of the scale (demand side) gains more weight relative to the supply side, while deflation sets in when total asset output (supply side)—especially everyday goods and services—outweighs the currency leg. In either scenario, if the money supply rebalancing mechanism falters, the system unravels: the demand side ceases to add weight as inequalities widen, purchasing power diminishes and people seek currencies with better balance, and eventually, the entire currency (and its economy) collapses. When that happens, either everyone has been migrating to another currency, or a new system emerges from the rubble.

Chasing demand differences

As you might have intuited, the total volume of divisible money doesn’t really matter. It’s issued money that could potentially be used, yes, but as long as the money units just sits there in people’s wallets—it’s essentially unemployed.

What actually matters is how people react—whether they use the money or not. Does it add weight to the demand side of the big-scale as a currency, flowing through spending in various asset markets? That all comes down to incentives, habits, and where people choose to put their money. Every time currency is spent in exchange for something, it tilts the demand-side tray of that money (its local velocity toward that thing), feeding into the broader currency velocity (its total velocity).

Conversely, if exchange coordination breaks down, people hold onto money, leaving it idle and off the big-scale entirely. No exchanges mean that money isn’t being used as an active currency, no resources are being traded with it, and its velocity crashes toward zero. And yeah, Alice grew her apples—costing her money, time, and effort—but if Bob (or anyone) won’t pay because that money isn’t actually changing hands as currency, the apples rot unsold. But before that, Alice’s patience and savings run out, and when that happens at scale, the supposed medium of exchange stops exchanging. The economy seizes up, and suddenly, you need a foreign currency that actually gets the exchange job done.

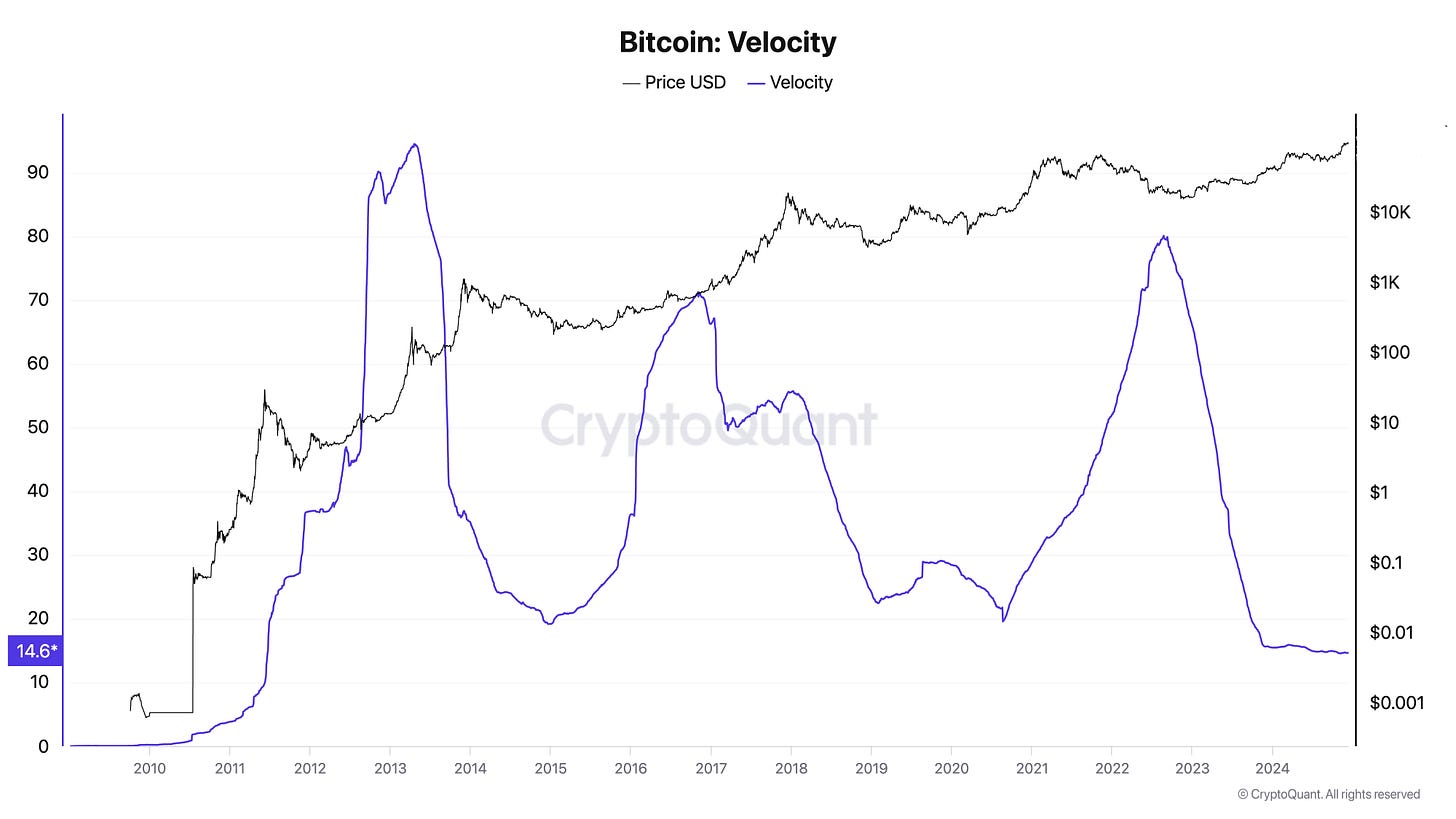

This means we cannot just assume a constant velocity over long periods—as Friedman’s Quantity Theory of Money might suggest [1], because, well currency usage as a medium of exchange isn’t always predictable or already established. Maybe it’s being swapped out for another currency because its policy is a mess [2], maybe there’s too much demand for financialization and speculation in financial contracts, not the real economy [3, 4], or maybe there’s barely any spending at all—just an unstable phase in the currency’s establishment [5].

Remember Satoshi Nakamoto breaking down monetary theory on November 8, 2008, just 9 days after launching the Whitepaper [1]6:

[1] Satoshi: The fact that new coins are produced means the money supply increases by a planned amount, but this does not necessarily result in inflation.

If the supply of money increases at the same rate that the number of people using it increases, prices remain stable.

If it does not increase as fast as demand, there will be deflation.

The rate (r) relationships Satoshi clearly described are:

From these, the following relationship can be deduced:

So, Satoshi’s input also confirms economic theory that the whole stability game of a currency depends first and foremost on the user base influencing its velocity, not the money stock per se [7]. Yes! That’s the “usage rate”, referring to how much of the total money stock people are swapping as currency, adding weight to the demand side of the big-scale as a medium for settling exchanges for real-world stuff/assets on the supply side.

This underscores why the system’s configuration around its balancing scale is critical. Let’s examine the primary factors that determine whether a currency can sustain stability and serve as the economy’s coordinating medium.

Monetary policy influence

Monetary policy is the primary factor shaping demand differences, determining whether the incentives it creates—paired with effective or ineffective policy execution—allow the scale to perform its balancing act or leave the scale economy empty or nearly empty and forced to depend entirely on off‐scale FX market demand.

If monetary policy is unpredictable and subject to market mechanics that dynamically balance with the supply the currency’s weight against local economic output—actual goods and services—the system can sustain itself. In a well‐functioning local economy, businesses and workers get paid, spend on necessities, settle debts, reinvest into productive capital and input goods, all reinforcing a healthy balance. Conversely, policies that encourage either reckless spending or stagnant spending can drain the scale and eventually break the system over time.

When policy is fixed and predictable, a fixed supply can transform the asset into a buy‐and‐hold investment. It discourages circulation as a currency, except for those who have no choice but to spend it on essentials. This dynamic turns the asset into a speculative instrument, attractive in off-scale FX markets for its scarcity—driving up its price and lowering volatility as foreign demand grows.

Without a proper feedback loop between supply and demand for real-world things, two scenarios may occur in the local economy:

Case 1. An asset born with a predictable fixed supply will fail to adequately fill or stabilize the scale an its local economy from the outset.

Case 2. A functioning currency that later fixes its supply will gradually see its scale empty of economic activity.

In both cases, without a supply feedback loop for real payments usage, its purchasing power will always be volatile and dependent on foreign currency conversions.

Distribution policy influence

The second factor is the distribution of the currency among agents, which in turn determines the weights of spending, the local velocities on the currency leg of the scale—as people respond to system’s built‐in incentives based on their needs, habits, and spending preferences once money hits their pockets.

The decision is whether to flow the currency via spending, save it to invest or finance others, speculate wildly riding the price waves, or simply sit tight holding the bag. If spending, are we talking about a bag of groceries to feed the family, splurging on the latest Apple AR glasses only a few can afford, or borrowing to go all-in on a meme coin index? Each choice sends ripples through the economy and its productivity, tipping the scale toward essential goods, luxury items, or outright casino vibes in financial contracts or other assets. It’s all about where you play your stack!

Think of it as the playbook for who gets their hands on freshly minted money in the primary market8, how much they get, and on what terms. It sets the tone for the whole game.

The real drama unfolds depending on whether there’s a good interactive dance between spending habits—which either drive demand for stuff or suppress it—and a supply that may respond dynamically or stays static to people’s demand reactions. This interplay, or balancing feedback loop, is crucial: if the dance goes well, it regulates inflation and deflation, maintaining value stability; if not, the result may be an imbalanced, unstable, or even non‐existent monetary economy.

Now, if you link the system’s mechanics to the inherent incentives it sparks in agents and their personal currency preferences—spend, save, or just sit on their money—you get a picture of why there may also be factors shaping heterogeneous aggregate demands that would better coordinate exchange in different community currencies. And for stability? That means a self-sovereign currency area tailored to each community. Let’s see some of those factors:

Climate variations. Weather shifts can alter spending patterns and frequency of transactions. Think of two zones in the same year period: one sweating through summers buying air conditioners, the other freezing in winters with soaring heating bills. Snow? Furnace fixes and ski trips. Tropics? Beach rentals and piña coladas. Same currency, wildly different spending patterns.

Demographics. Population size, age, and growth rates affect how often currency changes hands. A community full of young professionals might treat itself to new iPhones and pricey avocado toast—currency velocity soars. Meanwhile, a retiree-heavy region sees more savings and health expenses, slowing circulation. Each group’s distinct life stage shapes demand and how fast currency hops from wallet to wallet.

Cultural norms. In a region where “saving for tomorrow” is ingrained from childhood, fewer people splurge on personal drones or pricey milk tea runs, leading to lower “usage rates”. Conversely, a live-for-the-moment culture quickly spends currency on restaurants, concerts, and gadgets.

Connecting demand with supply differences

You probably saw this coming, but there are factors that can seriously disrupt and create major economic disparities on the supply side of any currency system’s big-scale. This is where all the real-world stuff tied to currency payments sits, shaping the entire economic structure and production processes. Every resource that goes into making goods and services—inputs for more goods and services—ends up here. Think about Starbucks sourcing coffee beans: first, farmers grow them and get paid, then distributors ship them and get paid, then roasters do their magic before baristas finally hand you your overpriced latte. Same with financial contracts—like Starbucks issuing bonds to fund 500 more stores and convince even more people they need caramel macchiatos. These are the trays of the scale, loaded with real, tangible stuff.

In a currency economy, it’s pretty obvious that the value of things traded through market scales ends up being related to, well, the currency itself—kind of the whole point of having a currency’s big-scale connecting both sides, right? So, naturally, on February 18, 2009, days after the previous message, Satoshi Nakamoto went ahead and called for the need to connect money supply management on the demand side—dynamically adjusting in a feedback loop to match its “usage rate”—to its use on the supply side, tied to the real world value of things or pegged to some things valuable in exchange [2]9:

[2] Satoshi:

DEMAND-SIDE MONEY USE:

There is nobody to act as central bank or federal reserve to adjust the money supply as the population of users grows.SUPPLY-SIDE STATUS OF REAL WORLD THINGS:

That would have required a trusted party to determine the value, because I don't know a way for software to know the real world value of things. If there was some clever way, or if we wanted to trust someone to actively manage the money supply to peg it to something, the rules could have been programmed for that.MONEY SUPPLY LOOP: BALANCING DEMAND-SUPPLY VALUE

In this sense, it’s more typical of a precious metal. Instead of the supply changing to keep the value the same, the supply is predetermined and the value changes.

What this boils down to is that currency value stability—specifically, the value reflecting the currency’s purchasing power in terms of real world things—is now just a matter of rebranding rates (r): how the money supply rate responds to the demand rate for real stuff in a nice feedback loop.

People like to think a currency’s value stability comes from deep, liquid FX markets off the local scale. If it doesn’t swing too much against other currencies, it must be stable, right? Not really.

What actually matters—and the reason Satoshi insisted on it—is the currency purchasing power stability within its own big-scale: the ability to consistently exchange with it real world things over time. Sure, high liquidity and low volatility in FX markets can help an asset gain traction, especially if it appreciates over time—driven by growing demand from foreign currencies like the U.S. dollar against the asset’s scarce supply available for sale. But being a liquid asset in foreign exchange markets just makes it, at best, a “store of foreign exchange value”. It still depends on converting into another currency to acquire stuff with that foreign buying power.

The independent store of value in purchasing power? That happens at the local big-scale level, where people actually use the currency steadily over time for exchanging real things—without relying on off-scale FX markets to convert it back and forth. So, purchasing power isn’t about how stable an asset looks on a chart when priced against foreign exchange—it’s about whether that medium can reliably buy stuff in the real economy. Here’s the catch:

Even the most liquid and supposedly stable asset in off-scale FX markets can be wildly unstable and unpredictable in terms of “usage” in real-world payments. Consequently, its local purchasing power becomes unstable, and the asset depends on foreign currency(s) conversions to stabilize payments, exchanging currency for real world things.

So, rebranding rates (r) how? Combine Satoshi’s originals in [2] on the demand and supply side into one, without changing a word, and you get the balancing loop that Satoshi so elegantly put: the supply changing to keep the value the same.

(−) Adjust the money supply as the population of users grows.

(+) Determine the value. Know the real world value of things.

If there was some clever way…to actively manage the money supply to peg it to something, the rules could have been programmed for that.

= The supply changing to keep the value the same.

So what’s Satoshi telling us with the rates (r) in this formula?

Clear! That any currency with stable value can’t have a fixed money supply rate, and that money supply can’t adjust blindly either—it has to factor in the “usage rate,” which now shows up as the growth rate of things demanded, adjusted for how the currency circulates toward real-world value things for exchange (things’ velocity rate).

In other words, instability or imbalance with inflation or deflation isn’t just about money supply changes—it’s about how that money supply interacts with demand for exchanging stuff:

The formula that Satoshi somehow described, pictured on our big-scale—where the money stock adjusts to balance the currency’s domestic economic value (a.k.a. its purchasing power over real world things)—would look something like this:

Then, demand velocity volatility matters—a lot! If something flows unstably—maybe it flows, maybe it doesn’t—and the supply doesn’t adjust accordingly, it’s bad at coordinating exchange stably, which is kind of the whole point and what defines a currency. Even worse if it has a fixed supply that makes people want to hold it, throwing a wrench into its use as a medium of exchange.

Why? Do the easy math: when the currency used to demand real world things swings wildly and unpredictably, that weight (or velocity of currency) on the demand side of the scale throws everything into chaos. Maybe it’s just the natural consequence of an absolutely scarce asset triggering hoarding incentives (Case 1), or maybe it’s just bad policy suddenly freezing the money stock—ignoring people’s spending and supply production—wrecking the scale balance (Case 2).

As a Case 1 example, check out the volatility of bitcoin’s transactional demand (velocity)—and with it, its potential spending power. The 1-year rolling total velocity rate has been riding unpredictably like a roller coaster, ranging between 90+ and 14.6 today. Predetermined-supply assets would suffer the same instability in total velocity as in local velocities, narrowed to just real goods and services (those real world things). You never know when someone’s going to put currency into velocity on the scale out of necessity or hoard everything they can off-scale in their wallets. It’s basically a lottery.

This volatility in currency velocity toward real world things directly affects the economic output—because when less weight gets added to the demand side without a proper counterweight on the supply side of things, the big-scale empties over time, and things start falling apart. That’s where the two cases arise:

Case 1. With a predetermined rigid supply, there’s always more incentive to HODL than to toss coins for exchange on the scale. After all, truly scarce assets aren’t exactly common, and when you have one, you’re not eager to part with it if everyone else wants it too. So, an empty scale with barely any coin weight—just a handful of trades here and there—stays empty because there’s no demand adding any asset counterweight in the supply. And if there’s no exchange, there’s no economy, just coins sitting there without local purchasing power.

Case 2. If it’s a currency but the supply policy misfires—drying up the supply balancing process—prices drop, businesses stall, and suddenly, apples rot, massage appointments go unbooked, and businesses shut down. And even if total velocity suddenly rebounds, don’t expect output to instantly recover. Businesses don’t just close and reopen overnight.

And what happens next? The currency’s purchasing power value, the cost of “a unit of all the stuff in the economy”, takes a hit. That decline, without a counterbalancing mechanism in the money supply rate, what prevents HODL incentives in the first place, only spirals downward from there.

Then, for any sustainable currency, the supply changing to keep the value the same—adapting to peg it to the real world value of things—is pretty important, as contextualized by Satoshi’s original monetary insights. So much so that why else would Satoshi contrast a stable-value asset with what he defined bitcoin to be, more like a precious metal where supply is predetermined and the value changes? And then, as in message [2], just days later on May 3, 2009 [3]10 , Satoshi reiterated that he had tried to pick some supply that would balance its value by making prices similar to existing currencies, but couldn’t without knowing the future state or value of those things.

[3] Satoshi: I wanted to pick something that would make prices similar to existing currencies, but without knowing the future, that’s very hard.

This whole dynamic that Satoshi explained somehow like this: “Hey, the money supply needs to adapt to the people using it and the real things it pays for to stabilize its value and prices. That’s why I wanted to program something dynamic but couldn’t without knowing the future value of those things. So I went with a predetermined fixed supply instead”. This isn’t about Satoshi throwing stones at his bitcoin’s rigid design, quite the opposite. It’s about justifying that bitcoin is the key first step—the hard monetary base serving as the neutral anchor for stable currencies that are self-sustaining over time. Just as being the most stable store of value has historically determined which currencies endure and which ones get replaced [11,12], this time won’t be any different.

This leads us to dive into examples of the factors that will shape the fabric and productive processes of real world things, the goods and services in each economy. These in turn impact purchasing power as the key ‘value’ metric for stabilization—because, let’s face it, economies aren’t all on equal footing:

Resource Endowments. The availability of natural assets determines their productive use or the need to exchange something (money) to access them. An oil-rich community with giant export revenues can stabilize local prices more easily than a tiny island dependent on pricey energy imports. When oil prices tank, that same community might scramble to rein in currency or risk inflation in other sectors.

Human Capital. Skilled labor drives growth. Think of a community currency that's highly concentrated, like a biotech hub churning out breakthroughs—great, right? But if the currency supply doesn’t keep up with demand, prices drop, and people start hoarding, waiting for better deals. Flip it: no investment in labor training means stagnant output, too much money, and not enough goods. Either way, trouble.

Climatic Variations. Weather extremes can wreck physical production. A hurricane hits a major shrimp-fishing region with its own currency, cutting the shrimp supply in half overnight. Without a proper currency adjustment, shrimp dish prices shoot up, and all those tourist spots famous for their special shrimp plates have to shut down.

Tech Progress. New production tech can boost output fast or make old industries irrelevant. In a car-dependent currency economy, factory robots can double production overnight—awesome, unless the money supply lags, flooding the market with unsold cars. But if you're still building by hand while AI factories crank them out, you're stuck with deflation or stagnation.

Local Characteristics. Seasonal or structural quirks in the local economy affect output cycles. Tourism economies are great—until they’re not. A tropical island thrives on tourist currency, but when a pandemic shuts everything down, money piles up with nowhere to go. Prices drop, businesses close, and workers leave. Then tourists want to return, but now there’s not enough money circulating, and everything’s suddenly overpriced for those who stayed. Maybe we need some money counterbalancing.

Takeaways

Now you understand that currency stability (and with it, sustainability) depends on a balancing act that can be shaken by forces on both sides of the big-scale. On the demand side, people’s incentives and purchasing behavior dictate whether they actually use the currency for exchange. On the supply side, real-world goods and services wait to be traded, subject to everything from resource constraints and their allocation in the economy to production bottlenecks. Either the money stock adjusts to keep that big-scale dance in balance, or forget about stable buying power. And over time, without supply adjustments responding to these forces, you don’t just lose stability—you lose power altogether. Just pure chaos.

When structural differences and demand-supply heterogeneities emerge between economies exchanging goods in local currency, Optimal Currency Areas (OCAs) should emerge and be experimented with, not be areas set in stone.

By the way, that flexibility is exactly the original idea Satoshi Nakamoto expressed for bitcoin adoption: virtual, non-geographic communities experimenting with new economic paradigms across multiple currency areas—rather than lumping everything into one static currency pot. Satoshi explicitly advocated for the establishment of bitcoin as the first step foundation—defining it as a basic P2P currency or base-layer currency for common settlement among communities’ programmable P2P social currencies, all with dynamic money supply [*]13:

I see Bitcoin as a foundation and first step if you want to implement programmable P2P social currencies like Marc’s ideas and others discussed here. First you need normal, basic P2P currency working. Once that is established and proven out, dynamic smart money is an easy next step. I love the idea of virtual, non-geographic communities experimenting with new economic paradigms.

The next ‘dynamic smart money’ phase could come once bitcoin was established and proven, along with finding a ‘smart’ or ‘clever way’ for not having to supply and manage money, self-balancing with the real world value of things. Something Satoshi couldn’t program using software alone.

Communities should be able to form organically through bottom-up economic organization, even virtually and non-geographically, to stabilize global exchange—as long as no external powers block the process from happening freely.

Now put it all together with Satoshi’s insights, and you get a clear picture of what bitcoin is and why it exists—to serve as the basis for a system that can handle all these deeply rooted heterogeneities explained here.

Satoshi laid out the economic theory: for value stability without inflation, the money supply rate has to adapt to the number of people using it toward things with real-world value. Satoshi repeatedly said he tried to program an adaptive supply but couldn’t without the system knowing the future state—the real world value of things. So, as Satoshi put it, bitcoin was the first key step—a basic P2P currency—toward making real that dynamic smart money vision he would love to see experimented with. But first, and hardest of all, bitcoin had to prove itself and get established as the base-layer asset of that future.

At its core, bitcoin is a cash-like monetary base, transferable peer-to-peer. It’s the essential basis for a system of community or P2P social currencies with a fractionally reserved, self-regulating dynamic supply, all without trusted central parties. Currencies redeemable in bitcoin as the basic settlement asset. This is the path Satoshi laid out for real bitcoin adoption. Without it, its real-world use will remain minimal and shaky, more of a speculative bet than a practical reality.

So sure, money being exchanged as currency can start being anything—as salt bars, dolphin teeth, tea bricks did in the past—but that doesn’t mean it’ll keep your economy afloat, let alone sustain itself being the reliable medium of exchange. That’s why any money base has always converged to better forms, with properties that make it more resilient. Meanwhile, a “dynamic smart” local balancing act has to sit on top of that base. That’s why we call currency, in fancy terms, a Complex Adaptive System. Push it too far, and you get economic crashes, wealth transfers, and social inequalities.

But let’s dive into all of that in later chapters. Stay tuned!

Share the project so others can think about money from first principles like you!

Friedman, M., 1956. The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement. In Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money. University of Chicago Press.

Calvo, G.A. and Végh Gramont, C.A., 1992. Currency substitution in developing countries: an introduction. IMF Working Papers, 1992(040), pp.1-32.

Minsky, H.P., 1986. Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Epstein, G.A. (ed.) 2005. Financialization and the World Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kiyotaki, N. and Wright, R., 1989. On money as a medium of exchange. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), pp.927-954.

Nakamoto, Satoshi. Bitcoin P2P E-Cash Paper. Email to the Cryptography Mailing List, November 8, 2008. metzdowd.com/pipermail/cryptography/2008-November/014831.html

Fisher, I., 1911. The Purchasing Power of Money: Its Determination and Relation to Credit, Interest, and Crises. New York: Macmillan.

The primary market refers to the initial distribution of newly created or issued money

Nakamoto, Satoshi. Bitcoin Open Source Implementation of P2P Currency. P2P Foundation, February 18, 2009. satoshi.nakamotoinstitute.org/posts/p2pfoundation/3/

Malmi, Martti. Satoshi - Sirius Emails 2009-2011. GitHub Pages. mmalmi.github.io/satoshi/

Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A., 1963. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Davies, G., 1994. A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Nakamoto, Satoshi. Re: [p2p-research] Bitcoin Open Source Implementation of P2P. Email, February 13, 2009. Satoshi's original: diyhpl.us/~bryan/irc/bitcoin-satoshi/email-p2presearch-2009-02-13-023120.txt